Course-of-values recursion

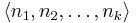

In computability theory, course-of-values recursion is a technique for defining number-theoretic functions by recursion. In a definition of a function f by course-of-values recursion, the value of f(n+1) is computed from the sequence  . The fact that such definitions can be converted into definitions using a simpler form of recursion is often used to prove that functions defined by course-of-values recursion are primitive recursive.

. The fact that such definitions can be converted into definitions using a simpler form of recursion is often used to prove that functions defined by course-of-values recursion are primitive recursive.

This article uses the convention that the natural numbers are the set {1,2,3,4,...}.

Contents |

Definition and examples

The factorial function n! is recursively defined by the rules

- 1! = 1,

- (n+1)! = (n+1)*(n!).

This recursion is a primitive recursion because it only requires the previous value n! in order to compute the next value (n+1)!. On the other hand, the function Fib(n), which returns the nth Fibonacci number, is defined with the recursion equations

- Fib(1) = 1,

- Fib(2) = 1,

- Fib(n+2) = Fib(n+1) + Fib(n).

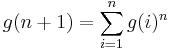

In order to compute Fib(n+2), the last two values of the Fib function are required. Finally, consider the function g defined with the recursion equations

- g(1) = 2,

.

.

To compute g(n+1) using these equations, all the previous values of g must be computed; no fixed finite number of previous values is sufficient in general for the computation of g. The functions Fib and g are examples of functions defined by course-of-values recursion.

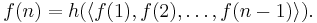

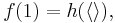

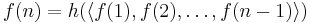

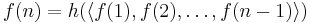

In general, a function f is defined by course-of-values recursion if there is a fixed function h such that for all n,

In this notation,

and thus the initial value(s) of the recursion must be "hard coded" into h.

Equivalence to primitive recursion

In order to convert a definition by course-of-values recursion into a primitive recursion, an auxiliary (helper) function is used. Suppose that

.

.

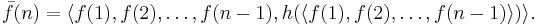

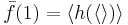

To redefine f using primitive recursion, first define the auxiliary course-of-values function

Thus  encodes the first n values of f, and

encodes the first n values of f, and  is defined by primitive recursion because

is defined by primitive recursion because  is the concatenation of

is the concatenation of  and the one-element sequence

and the one-element sequence  :

:

,

, .

.

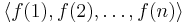

Given  , the original function f can be defined by letting f(n) be the final element of the sequence

, the original function f can be defined by letting f(n) be the final element of the sequence  . Thus f can be defined without a course-of-values recursion in any setting where it is possible to handle sequences of natural numbers. Such settings include LISP and the primitive recursive functions, discussed in the next section.

. Thus f can be defined without a course-of-values recursion in any setting where it is possible to handle sequences of natural numbers. Such settings include LISP and the primitive recursive functions, discussed in the next section.

Application to primitive recursive functions

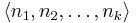

In the context of primitive recursive functions, it is convenient to have a means to represent finite sequences of natural numbers as single natural numbers. One such method, Gödel's encoding, represents a sequence  as

as

,

,

where pi represent the ith prime. It can be shown that, with this representation, the ordinary operations on sequences are all primitive recursive. These operations include

- Determining the length of a sequence,

- Extracting an element from a sequence given its index,

- Concatenating two sequences.

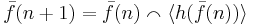

Using this representation of sequences, it can be seen that if h(m) is primitive recursive then the function

.

.

is also primitive recursive.

When the natural numbers are taken to begin with zero, the sequence  is instead represented as

is instead represented as

,

,

which makes it possible to distinguish the codes for the sequences  and

and  .

.

References

- Hinman, P.G., 2006, Fundamentals of Mathematical Logic, A K Peters.

- Odifreddi, P.G., 1989, Classical Recursion Theory, North Holland; second edition, 1999.